Many writing teachers believe in the value of spontaneous, on-the-spot writing, and I’m among them. Every July, I run Write in the Garden, a one-day writing workshop in my backyard. At the start, we introduce ourselves and discuss principles of writing, and then I give prompts — at first, short ones, just a few minutes, asking participants not to think, just let it flow, to scribble out whatever comes to them. (I believe old-fashioned pen and paper are far better than devices for this type of work.) Next a few longer prompts, and then the writers are invited to read what they’ve written to each other, although reading is always optional and voluntary. It’s important there’s no pressure to perform. This kind of writing is for the writer only.

After lunch, the prompts are longer, and people scatter to the corners of the garden to sit in tranquillity and see what comes. And very often, what comes is surprisingly rich and vivid. It’s a powerful experience to give yourself time to think in silence, to get in touch with what’s going on inside, with memory. How often, in our busy lives, do we make that vital time?

For one prompt, writers are invited to pick folded pieces of paper on which are written colours to inspire memory and story: red, blue, green, black, white. I tell them that when my friend Wayson Choy was studying at UBC with the superb writer Carol Shields, she gave them this assignment. Wayson’s word was pink. From that prompt came a short story, The Jade Peony, which he later expanded into his enormously successful first novel.

Once when we did this in the workshop, I wrote too. My paper said silver. What follows is the on-the-spot story that emerged from this prompt, a bit meandering and unfocussed, as this kind of writing usually is. A year later, I reread it and thought, Hmm, I could do something with that. I did some research, worked to make the beginning and ending more vibrant and pointed, and expanded it into an essay for the Globe and Mail.

On-the-spot writing is valuable. You never know what will surface. Pick a word; don’t think, just let your pen flow across the page, and see what comes.

Why not try it?

Red blue green black white pink silver. Pick one. Go.

On the spot writing about silver.

My mother grew up in an English village; her parents were the village schoolteachers. Especially through the war, the family had very little. They owned and used a few lovely old things from grandparents, a silver teapot, old English platters and bowls, but not much.

When Mum married my father, her parents were concerned and disappointed — she’d chosen not only an American, but a Jew. Ah well, said my grandmother, Jews make good providers. And so it was. My dad died at only 65 after 39 years of marriage, leaving my mum comfortably well off for the rest of her life. 24 more years.

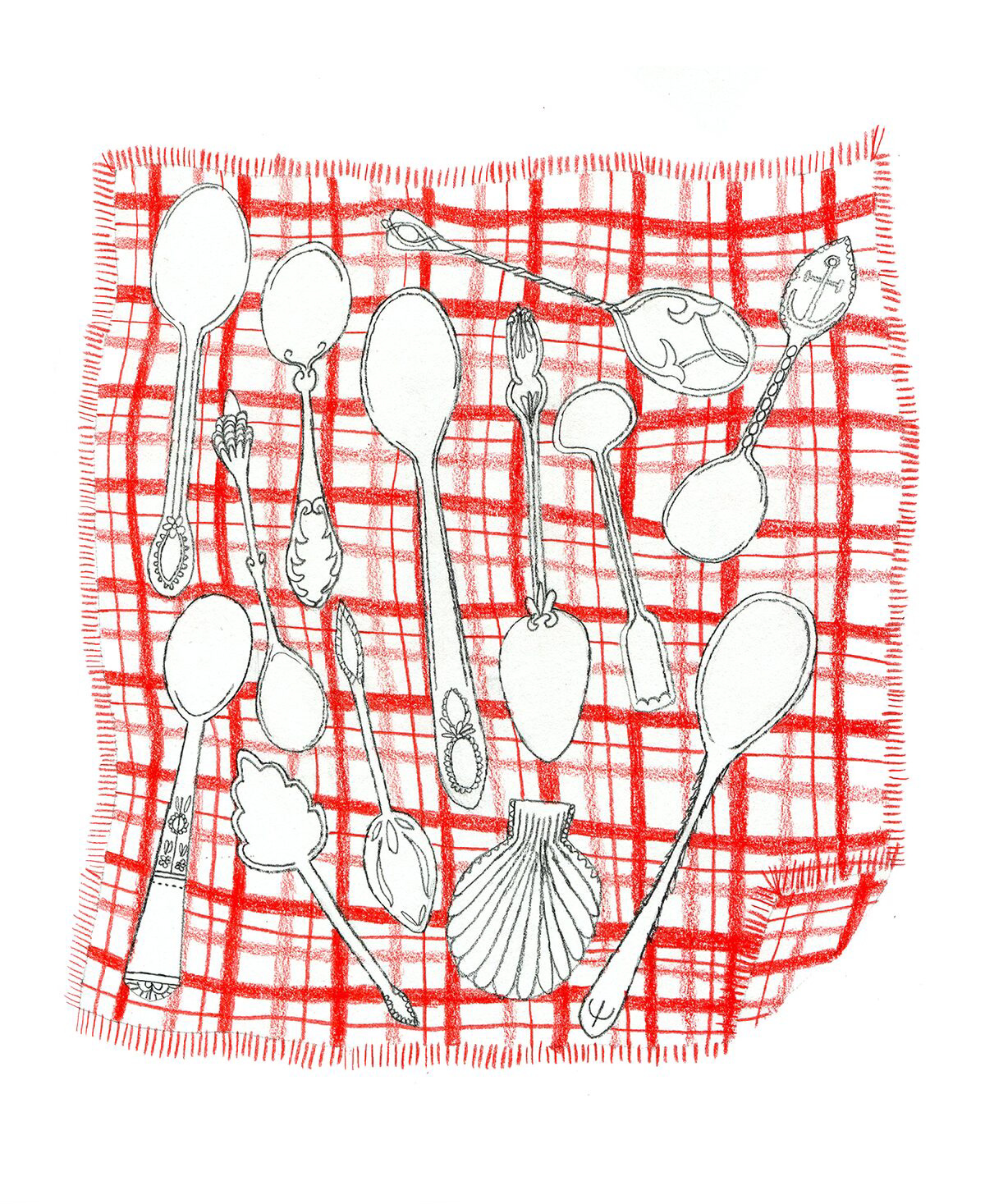

One of the things she did during those years was buy spoons, silver spoons with hallmarks, Georgian, Victorian, older. She went to thrift stores and garage sales and antique stores, and she bought beautiful slender silver spoons, big, medium, small. But she didn't use them. She wrapped them carefully in soft blue cloth and hid them in a trunk in her closet, under old winter clothes. Every so often she’d take them out, polish them, add any new ones to the stash, and wrap and hide them again. One spoon, she told us, was particularly valuable, from the 1600s.

After she died my brother and I unearthed the spoons and other buried items, silver jugs and bowls. We wanted to sell them, hoping they'd be worth a lot. But we found out nobody wants silver these days. Too much work to polish. The dealers buy even the loveliest old things just to melt them down. My mother would weep.

One year I went to London to visit friends, taking the valuable spoon with me. I made a special trip to The Silver Vaults, a huge underground shopping mall exclusively for silver: tea sets, trophies, cutlery. I found the spoon man and proudly showed him Mum’s treasure.

“Oh I have lots of these,” he said. “1860 or so. I'll give you forty pounds.”

I kept the spoon. It accompanied me in my trip around Europe — me and my spoon. Now it lives with Mum’s other spoons in my cutlery drawer. I don't even remember which one it is. I use the spoons every day.

For a long time it looked as if neither of my children cared about the things I inherited from my parents, including the spoons. But recently my son developed a huge appreciation for old things. He loves the old photos, the artifacts, the souvenirs. He loves the spoons.

THE ROMANCE OF SILVER

And of London’s Silver Vaults

The Globe and Mail

Down I went, down the stairs into an underground cavern, stepping through heavy steel security gates with an armed guard keeping watch. I was entering the London Silver Vaults, a unique shopping mall beneath Chancery Lane, the largest retail offering of old and new silver in the world. Scores of silver dealers in a row, one after the other in their individual “vaults,” shop after small shop filled with glittering treasure, the dealers looking out hungrily at the few shoppers strolling by, including me. At the back of some shops, almost out of sight, were workers busy polishing, polishing, polishing. Mole people, I thought, who rarely see the sun.

I could see myself reflected in platters and bowls, ornate tea sets and silver-framed mirrors as I walked past, looking for the cutlery specialist. Deep in my handbag was my mother’s special antique spoon, wrapped in a soft blue cloth.

My beautiful six-foot-tall mother loved and collected old English silver spoons. She had many collections, including, to name a few, magazines, recipes, clean empty yogurt containers, knee-high stockings, letters, cut-out newspaper articles, dressy white blouses and unopened perfume bottles given to her through the decades as gifts. But her favourite collection was British spoons. In the 24 years between my father’s too-early death at the age of 65 and her own death at 89, she haunted antique stores, thrift stores, estate sales and open-air markets. She bought miniature lead farm animals, pretty ceramic jugs, vases, pots and many other things. But most of all, she hunted spoons.

Mum knew all the hallmarks stamped on the handles, like the “lion passant,” that means genuine British sterling, and the “crowned leopard” made in London before 1820. She carried a large magnifying glass in her purse so she could inspect and check. Size didn’t matter; she bought delicate coffee spoons, slender soup spoons, heavy serving spoons and the occasional ladle. She bought a stuffing spoon with an extra-long handle for shoving into the cavity of a turkey or goose and, in a fanciful moment, she bought some ornate silver fish knives. The collection grew.

Why did my mother nurse this particular fixation? She’d grown up in an English village; her parents, the village schoolmasters, were respectable but poor and the family had little money and no luxuries. They did own a few lovely family heirlooms: a needlepoint sampler from 1846, Nana Bates’s silver-plated teapot. After the war, to the huge disappointment of her parents, my mother immigrated to North America, married my American father and stayed in the New World. But even after a lifetime in Canada, she remained British to her core. Perhaps the hunt for old English spoons was a search for her country and her past, or her acknowledgment of an ease with money and consumption that her parents never had.

In any case, she loved her spoons.

But strangely, she did not use or display these cherished items. Although after Dad’s death she lived on the 12th floor of an Ottawa condo building with a locked main entrance, still, Mum was paranoid. She was afraid thieves would come for her spoons. Wrapping them carefully in cloth or soft bags, she stored them under old winter clothes in a locked trunk in her cleaning-supplies cupboard.

I thought she was crazy. My brother and I had no interest in old British silver of any shape or size, and I couldn’t understand my mother’s passion for cutlery and her other obsessions. I wanted her to stop shopping and to use and enjoy what she already had. Occasionally, when I’d flown in from Toronto to visit, she’d take her treasures out to show me, to polish and to add new ones to the stash. I saw that she’d helpfully attached little labels, I guessed for us when she was no longer there. “1810 soup ladle bought in Victoria, gorgeous Georgian,” said one. “Stuffing spoon, 1812, London, beautiful shaped handle.”

One, in particular, she was especially proud of and liked to show off, the oldest of them all, she explained, probably from the late 1600s. As I felt its smooth weight in my hand, I realized the great diarist Samuel Pepys might have slurped his soup from this very spoon and felt a hint of her excitement.

After she died, my brother and I had the huge job of sorting through her treasures and non-treasures. One day we opened the trunk and hauled out the heavy silver stash. We each chose a bit for ourselves, although mostly, because neither he nor I had much money, we were hoping to sell the bulk of it to an antique dealer. Disappointment was immediate. Nobody, we discovered, wants silver these days, too much work to polish. Dealers will buy even beautiful pieces of antique silver only by weight, to melt them down.

My mother would weep. All those hours of searching and purchasing and polishing and, occasionally, admiring. No, we couldn’t allow her finds to be destroyed. We sold a few clunky pieces neither of us liked and divided the rest to keep.

But we still had hopes for that precious Samuel Pepys spoon and I decided to visit friends in London and see if I could sell it there. Hence, the Silver Vaults. This rare treasure, my mother’s greatest find, would surely excite a dealer. He’d offer a ridiculous amount for it and my brother and I would toast Mum and her magnifying glass with champagne.

“Oh I have loads of those,” said the cutlery man, glancing at the treasure I’d pulled from my purse and unwrapped. “From the mid-1800s. I’ll give you £40.”

Less than Mum paid for it. A reminder that sometimes, about this and other things, my mother could be wrong.

I thanked him, rewrapped the spoon and walked up out of the Silver Vaults into the sun. Wherever I went in my travels that spring, Mum’s spoon came with me. At home, I put the once-special implement with the others in the drawer with cutlery I use every day. Now I don’t even remember which one it is.

But every time I slurp my soup with a newly polished Georgian spoon or stuff our Christmas turkey with the one with the long beautifully shaped handle, every time I dust my own collections, displayed on open shelves – Fiestaware, baskets, folk art, old children’s books, scores of framed family photographs – my mother, with all her brilliance and all her flaws, is with me.

You found a way to weave her most precious find into your life, and it means so much more than the piddling sum the dealer offered. This essay delights on many levels.

Always a pleasure to read your work Beth. I love prompts and how they can turn into wonderful stories like the one you wrote. I had a similar experience with a prompt of a photograph that turned into a First Person story in the G&M about my mum and her connection to the Battle of the Somme.